RON LAIRD

Birthday: May 31st, 1938

Current Residence : Ashtabula, OH

Hometown: Louisville, KY

PRS

Outdoors

10 km - 43:07

20 km - 1:28:18

Perseverance is Ron Laird’s middle name. Unable to qualify for his high school baseball team, he joined track and ran the half mile and mile, but his running wasn’t much better than his baseball. Fort unately, Laird had other talents. While attending Parsons School of Design on a six-week art scholarship during the summer of 1955, Laird competed at AAU track meets just outside Yankee Stadium. At only 50 cents to join the AAU and 25 cents an event, he competed in all the events he could handle.

Running a few events and then throwing the discus and javelin, Laird noticed people warming up for the race walk. After mimicking their technique, he decided to give it a try. This race was handicapped, so slower walkers were granted a head start. As Laird had never race walked before, he began with a 600-yard lead. Still, Laird finished dead last. Only 17 years old at the time, he wanted to quit race walking, but two of his competitors (Elliot Denman and Bruce McDonald) talked the young athlete into pursuing the sport.

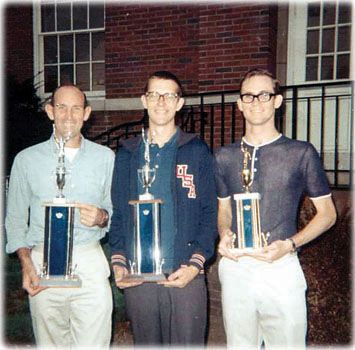

Embarrassed by the gait of race walking, Laird made progress by training at night. After a few more handicapped races, he felt ready for his first non-handicapped race, a 5K against the legendary Henry Laskau. Laskau’s friendliness and accessibility impressed him. However, when race time came, Laskau was ruthless, lapping Laird three times. Still, the experience and encouragement Laird gained convinced him that he should try a 10-mile handicapped race in Philadelphia. With two weeks of training, Laird entered the race and won. He was elated, having never earned a trophy or prize before.

Returning to school his senior year, Laird decided not to compete in high school activities. Instead, he joined the New York Pioneers and trained for the race walk. A series of indoor races at the Armory and Madison Square Garden kept him busy. His biggest race of the season was the 1-mile Nationals, where he finished 5 th with a time of 7:14.

Having great speed but little endurance, Laird headed to the Olympic Trials in 1956. Racing both the 20K and 50K, he struggled to finish the second race and needed to sit down several times. Determined, he marched towards his goal: a finisher’s trophy. (Laird did like his trophies.) Back then, aid stations at races were nonexistent. Laird, ever resourceful, convinced a bunch of kids who were harassing him to help. They rode their bicycles to a gas station and filled empty coke bottles with water.

Laird continued to improve after the trials. He raced often and trained hard. Dropping out of college, he ended up in the Army as a draftsman.

By 1958, Laird had placed first in the 20K Nationals with a time of 1:40:09. This achievement qualified him for his first international competition, a dual meet with the USSR. Qualifying for the team meant he earned a USA team uniform, expense-paid travel, and a two-dollar-a-day stipend. He began with the team training for a week at West Point. However, flying to Moscow and then racing against the 1956 Olympic champion Leonid Spirin must have been intimidating. Laird didn’t race up to his potential, walking a 1:49.

Next Laird was scheduled to race a 20K in Warsaw. However, then as now, the race walk received little respect. When officials wanted to watch other events instead of working the 20K race, they cancelled the competition. To make amends, George Hausleber invited the walkers to the national sports center, where they enjoyed themselves tremendously.

Laird soon finished his Army obligation and temporarily settled in Norristown, Pennsylvania. Unable to find steady employment, he worked where he could. He trained on the roads of the local mental institute and, sponsorless, hitchhiked to races.

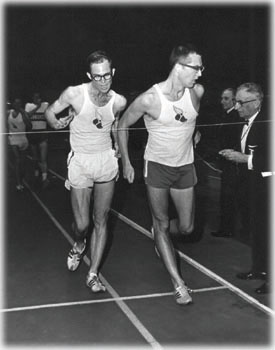

Laird continued to grow stronger and by the 1960 Olympic Trials was well prepared to qualify for the Olympic team. He won the 50K, the first of the two trials, without trouble. At the 20K trial, he found himself in third place late in the race. Knowing a third-place trials finish would require him to compete in both Olympic races, he stopped to wait for the next competitor, Bruce McDonald. McDonald, who had also qualified in the 50K two weeks earlier, came across Laird lying on the ground. Concerned there was a problem, he was relieved to learn Laird’s plan and joined Laird in waiting. When Bob Mimm caught them, they let him pass and finish third, relieved they would not be forced to race a double at the Olympics. In the end, Laird finished 19 th at the Games with a time of 4:53:21. Today he views the race as his finest Olympic achievement.

By 1962, Laird had obtained the New York Athletic Club (NYAC) as his sponsor and moved to Chicago to once again prepare for the Olympics. NYAC provided him funds to travel to many national meets. Instead of using the payments to cover his fares, however, Laird chose to return to hitching and pocket the cash.

Laird used many unconventional methods to improve performance. A favorite was the tire pull, an exercise he employed to strengthen his hamstrings. It required race walking with a rope and tire tied to his waist. Lacking any knowledge of exercise physiology, Laird pursued all training at a brutal, full-effort pace. He knew nothing of periodization and varied workouts. And while some of the techniques Laird used to gain speed differ sharply from those we use today, others are quite the same. One technique that has gone by the wayside is how Laird pulled his heel back, even before it hit the ground, and then dug it in. This allowed him to maximize his pulling power. However, just as we do today, he did turn his hips to extend stride.

In late 1963 Laird moved to California and decided to race at the 20K distance. After all, most 20K races required travel. He won the 1964 Olympic Trials and things looked on track for his second Olympic appearance. Unfortunately, his debut at Tokyo soon became the worst day of his racing career. Up until then, he had been disqualified only once before—quite an accomplishment, considering it took only one judge’s opinion to get pulled from a race. While he began the Tokyo race strong, something about his technique caught an official’s eye and cost him his second lifetime DQ. Meanwhile, Ron Zinn, his fiercest competitor from 1960 to 1965, finished sixth with a great personal record of 1:32.

Laird achieved perhaps his best international performances in 1967. The first race was at Lugano, in East Germany, a meet later renamed The World Cup. Midway through the 20K he led the pack with two Russians in tow. But a white flag and the still-fresh memory of his Olympic disqualification caused him to back off. He finished third with a time of 1:29:12, setting the first sub-1:30 American record in the process. Later that year, just before Mexican race walkers became dominant, Laird earned one of a duo of gold medals at the Pan American Games, with teammate Larry Young winning the 50K.

At the 1968 Olympic Trials, Laird had the pleasure of winning the 20K twice. (That’s right, twice.) The first trials were at sea level, and a spot on the Olympic Team was originally guaranteed to the winner of that race. Late in the race, Laird caught Larry Young hurling and nailed him, winning by five yards. Next, the top sea-level finishers were invited to a training camp and second trial race at altitude. There the athletes voted not to count the results of the sea-level race. Laird needed to race again. Justly, he won a second time.

The trip to Mexico City for the Olympic Games did not go as well, with Laird contracting strep throat early in the trip. Ironically, on race day he led the pack the first 2000 meters before breaking away and making a wrong turn. He walked a long 50 yards off course before doubling back and rejoining the race. He then faded badly, finishing near last.

Hoping to make up for his poor Olympic performance, Laird strove to make the team again in 1972. However, a hamstring injury obtained at an insignificant race put an end to his dreams. (A sad lesson to us all). He was forced to drop out of both Olympic Trial races and attend the Munich Games as a spectator. But the crafty Laird’s Olympic story does not end there. His twin brother was able to acquire a press pass for the games at a cost of one bottle of whiskey. The pass and Laird’s USA uniform gave him near-complete access to the entire Olympic compound, and he put it to good use.

After a year of nursing his hamstring back to health, Laird, 38, needed a new plan to combat his young and ever-improving peers. In fall 1975, he drove to Mexico City to join a small group of elite race walkers training for international competition. The group included the likes of Raul Gonzales and Daniel Bautista. Laird’s training strategy worked and he finished the 1976 Trials second only to Todd Scully. For a change, Laird’s performance peaked at the best time. He was the first American 20K finisher at the Games.

Laird’s competitive career was all but over by the 1980 Olympic Trials. He finished second to last but was disqualified after the finish. With racing behind him, he enjoyed the honor of leading a race-walking colony of 14 walkers at the Colorado Springs Olympic Training Center from 1981 to 1984. More a manager than coach, Laird provided technical advice and helped obtain sponsorships for the walkers, who essentially trained themselves. Laird recalls that group members were not always happy. Some walkers were incompatible and refused to work together.

When all was said and done, Laird set or reset 81 U.S. records, from the 1 mile to the 25 mile. In 1986 he became the first race walker inducted to the U.S. Track and Field Hall of Fame. He currently lives in northeast Ohio and walks an hour or two per day for fitness. (Race walkers beware: Laird is considering a Master’s comeback.)

1976

1st - 1:29:41

1975

8th - 1:31:50

1974

5th - 1:33:51

1973

1st - 1:30:27

1971

4th - 1:34:26

National rankings were not recorded prior to 1971

1973

5th - 4:35:51

National rankings were not recorded prior to 1971

1976

2 mile - 13:37.0

1971

1 mile - 6:24.9

1968

1 mile - 6:16.9

1964

1 mile - 6:22.7

1976

5K - 21:09.4

10K - 45:06.9

15K - 1:08:49

20K - 1:33:53

25K - 1:59:09

1975

1 hour - 8m 612 yards

5K - 22:08.6

25K - 1:56:38

1971

1 hour - 8 mi 80 yards

10K - 47:10.0

25K - 2:01:48.4

1970

30K - 2:37:17.4

1969

2 miles - 13:31.4

1 hour - 8m 20 yards

10K - 45:14.2

15K - 1:06:44.4

20K - 1:33:40.4

25K - 2:02:32

30K - 2:29:23

35K - 2:55:56.8

40K - 3:33:56

1968

1 hour - 7m 1386 yards

15K - 1:09:03

20K - 1:33:00

1967

2 miles - 13:41.4

10K - 45:29.2

1 hour - 8m 141 yards

15K - 1:08:13

20K - 1:38:40.4

25K - 1:59:18

30K - 2:29:05.6

35K - 2:57:40

1966

2 miles - 13:52.6

15K - 1:11:27.2

25K - 2:06:16

35K - 2:55:49.6

40K - 3:31:14

1965

2 miles - 14:04.2

1 hour - 7m 1432 yards

15K - 1:13:24.8

20K - 1:38:38

25K - 2:01:42

30K - 2:41:17

35K - 3:07:09

1964

1 hour - 8m 159 yards

20K - 1:34:44

30K - 2:26:27

1963

15K - 1:12:13

20K - 1:34:52

25K - no time

1962

35K - 3:20:21

50K - 5:25:30

1961

25K - 2:11:36.3

30K - 2:29:39.8

35K - 3:28:05

40K - 3:48:05

1960

40K - 3:45.16

50K - 4:40:09

1959

40K - 3:53:22.5

1958

20K - 1:40:09

25K - 2:16:05

50K Olympic Games

1968 - 25th - Mexico City

1964 - DQ - Tokyo, Japan

1960 - 19th - 4:53:21.6 - Rome, Italy

20K Olympic Games

1976 - 20th - 1:33.27.6 - Montreal, Canada

20K World Cup

1973 - 3rd - 1:30:45.0 - Lugano, Switzerland

1967 - 3rd - 1:29:12.6 - Bad Saarow, East Germany

20K Pan Am Games

1967 - 1st - 1:33:05.2 - Winnipeg, Canada

1963 - 4th - 1:52:09 – Buenos Aires, Sao Paulo