It's All About the Hips

Elite race walkers generate their primary source of forward locomotion from rotating the hips. Repeatedly pivoting the hips forward causes them to act as the body’s motor, propelling it forward one step at a time. Actively swinging the hip forward lengthens the stride from the top of the legs, while increasing stride length behind the body.

In a flexible race walker, the gain can be as much as three inches per stride. If you add as little as 1 inch to a typical 1-meter race walking stride, the net gain is approximately 10 meters per lap on a track. In a 20km race, that totals to over 500 meters gained. At an elite level, the savings is close to two minutes. In the last three Olympic Games it made the difference between a gold medal and finishing well off the podium.

An efficient race walker has more of their stride behind their body than the front. This is directly due to hip rotation. Good forward hip rotation is a key solid race walking technique.

The value of pursuing increased stride length was illustrated when Tim Seaman trained with Jefferson Perez, the 1996 Olympic champion and 2008 Olympic silver medalist. They measured their stride lengths and found that, while Jefferson is shorter than Tim, Jefferson’s stride length was 1.25 meters and Tim’s was 1.11 meters. That corresponds to Tim having to take 18,000 steps in a 20km race and Jefferson having to take only 16,000.

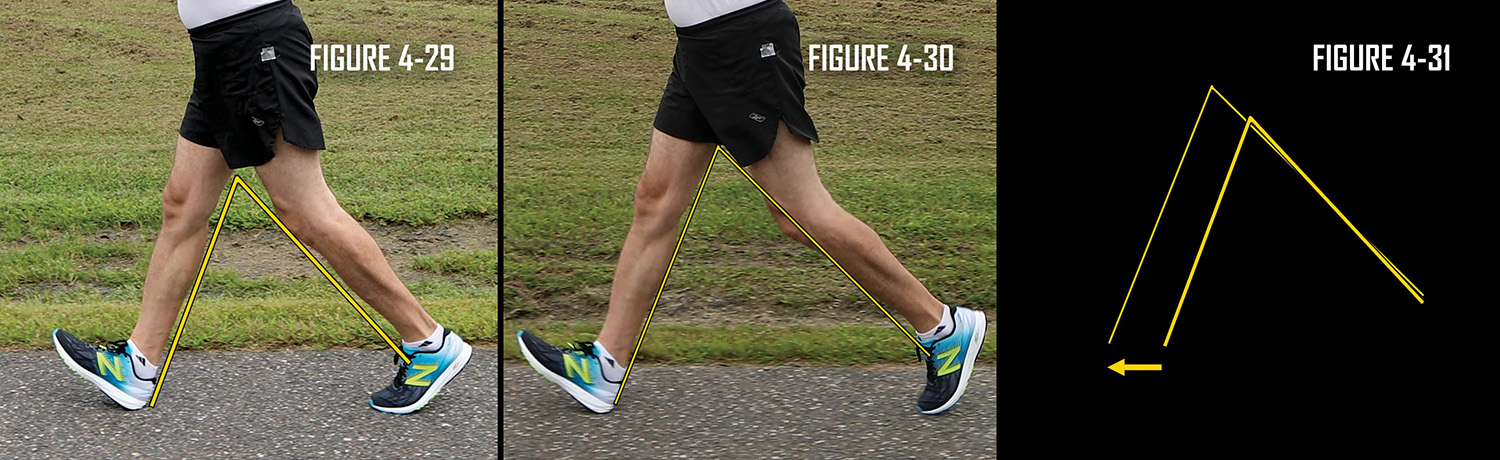

Observe the Figure 4-29 and 4-30. Both show the stride of the same race walker. The difference is the walker in Figure 4-30 is properly utilizing his hips, while the walker in Figure 4-29 is underutilizing them. Looking at the two photos, the difference is subtle. However, when comparing the strides side by side (Figure 4-31) the difference in stride length when utilizing proper hip rotation is obvious.

Some coaches tout that increasing hip rotation decreases a race walker’s cadence. This is an inaccurate evaluation of biomechanics. The hip rotates forward at the same time as the leg swings forward. The leg does not swing forward before the hip rotates. Since the two motions occur simultaneously, any reduction in cadence is minimal and greatly outweighed by the increase in stride length.

The exact motion of the hips during race walking is a bit complicated. The hip moves in three dimensions; its primary movement is forward, but it also must move slightly in and out as well as up and down. To further understand proper technique, observe the hip motion from varying perspectives.

A small circular sticker on the outside of the center of the hip is a great way to observe how the hip moves as the walker progresses through the stride. We start with the center point of the right hip as a race walker plants his heel on the ground (Figure 4-32).

As the body moves forward over a straightened leg, the center point of the hip rises until the straightened leg passes directly beneath the body (Figure 4-33).

From the moment the leg passes under the body until the right foot’s toe pushes off the ground, the center point of the hip moves downwards (Figure 4-34).

As the rear foot starts to swing forward, the leg must be bent (Figure 4-35).

This bent leg swings forward as the hip continues to lower slightly (Figure 4-36). This is known as “hip drop” and, while necessary, is a minimal action.

After the knee of the swing leg passes under the body (Figure 4-37), the center point of the hip rises to the neutral position (Figure 4-38).

Next Lesson: Hips Continued

Quick Link: Race Walking Arm Motion

Quick Link: Overall Stride