Violating the Loss of Contact Portion of the Definition of Race Walking

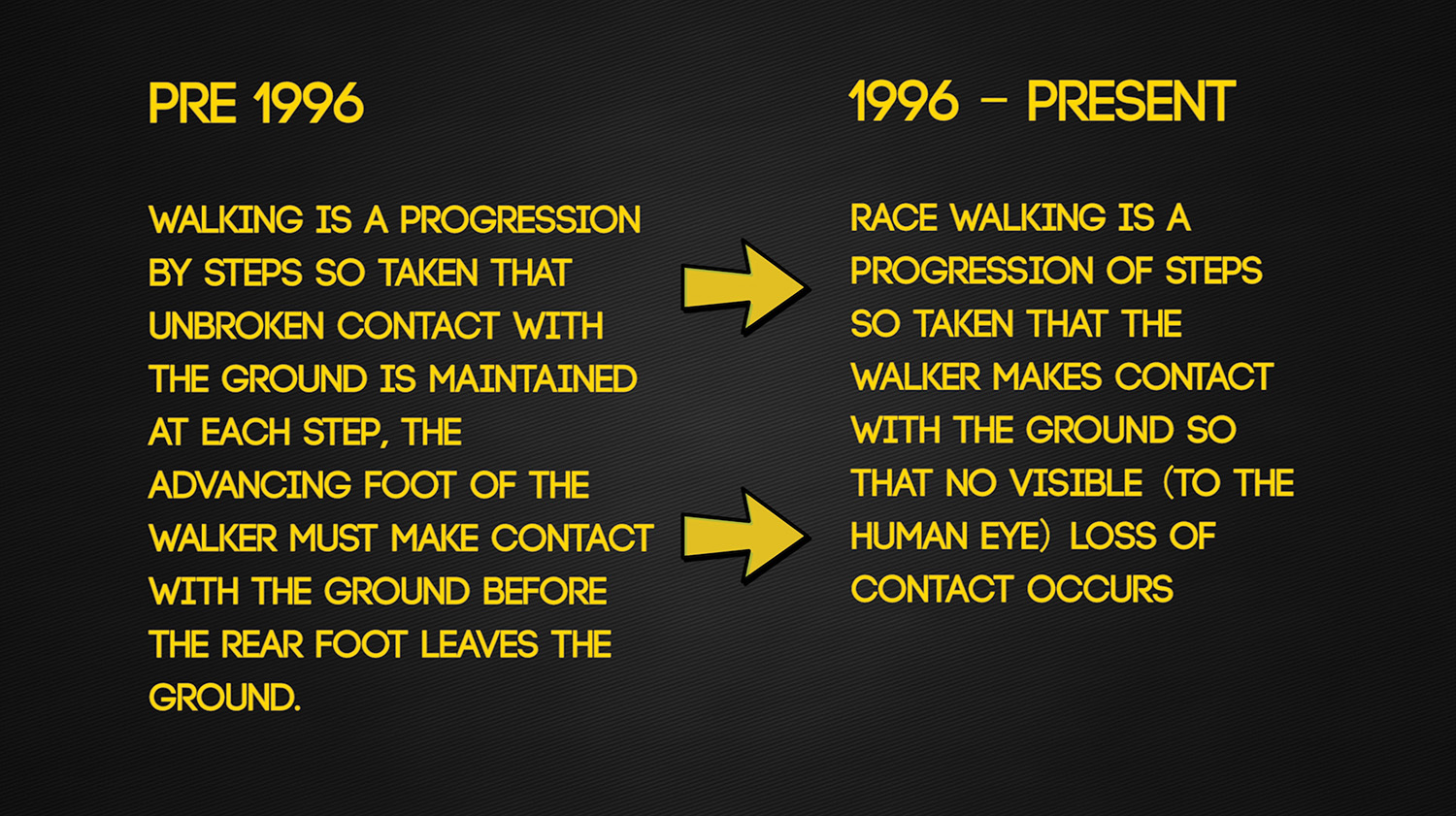

The definition of race walking has changed many times over the years. However, since the 1996 change in the definition of race walking, the determination of whether a race walker loses contact with the ground has become more subjective.

Because the definition now states that “the walker makes contact with the ground so that no visible (to the human eye) loss of contact occurs,” it is now impossible to state quantitatively whether a race walker is in violation of the definition of loss of contact.

What one human eye perceives, another may not.

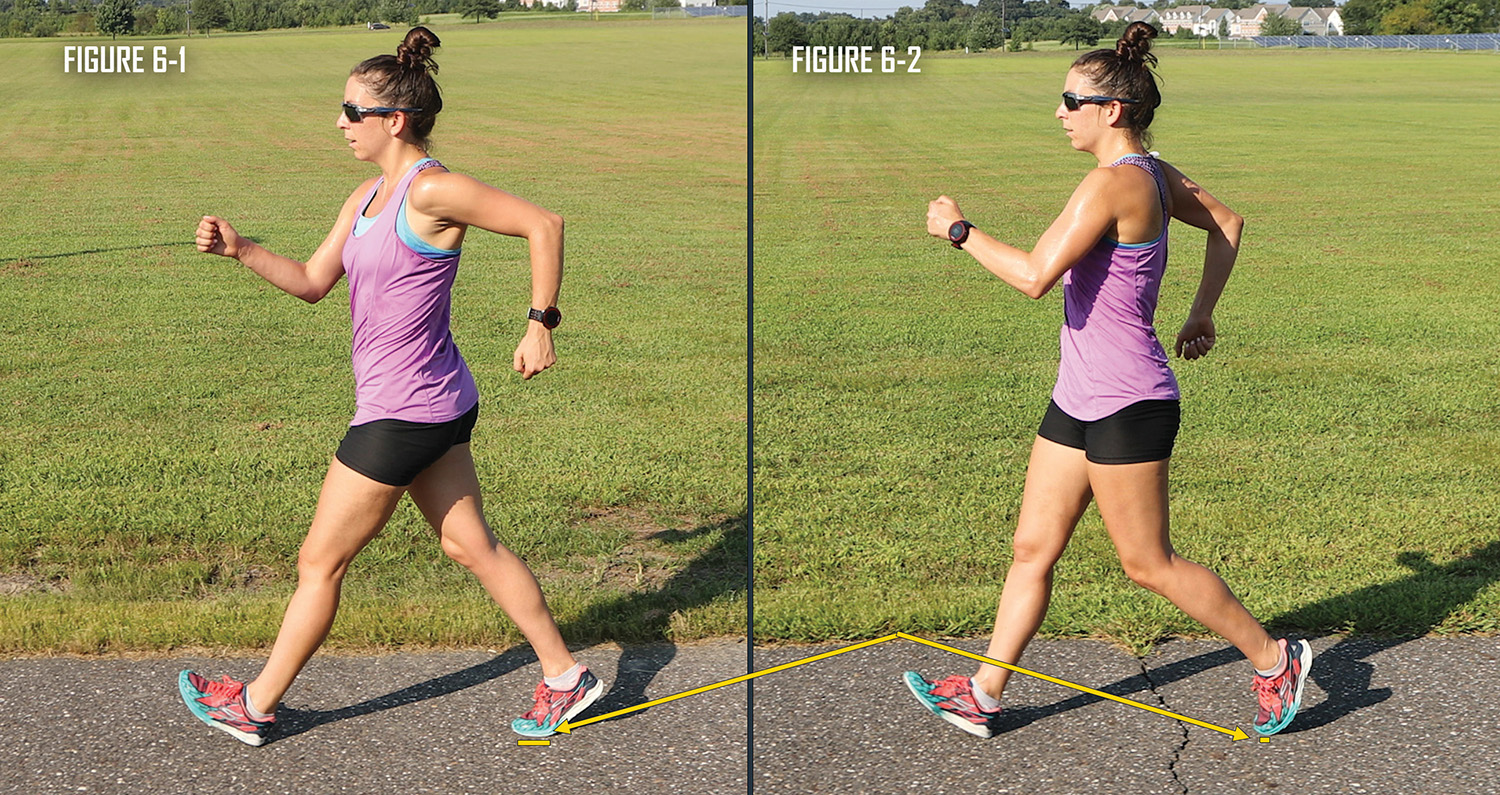

When a walker has a visible contact phase, which is significantly different than saying to look for a visible loss of contact, the answer is easily quantifiable. Let’s look at these two walkers. The walker in Figure 6-1 has a pronounced double-support phase. When the swing leg’s foot makes contact with the ground, the rear foot has not completed rolling up for toe-off. Instead, there is an extended period where both feet are in contact with the ground. This extended double-support phase allows a judge to easily discern a visible contact phase.

In contrast, if we look at the walker in Figure 6-2, whether there is a loss of contact is more difficult to discern with the human eye. She still has a moment of double contact, but it is only for an instant. Notice she has rolled up onto her toes at the moment the forward foot contacts the ground. This makes it difficult for a judge to observe accurately whether the walker has a visible contact phase in their stride.

A qualified judge should still be capable of identifying these walkers as they conform to the definition of race walking whether using the definition from before 1996 or the current definition. This is because with the new definition, the judge is not looking for visible contact but a visible loss of contact.

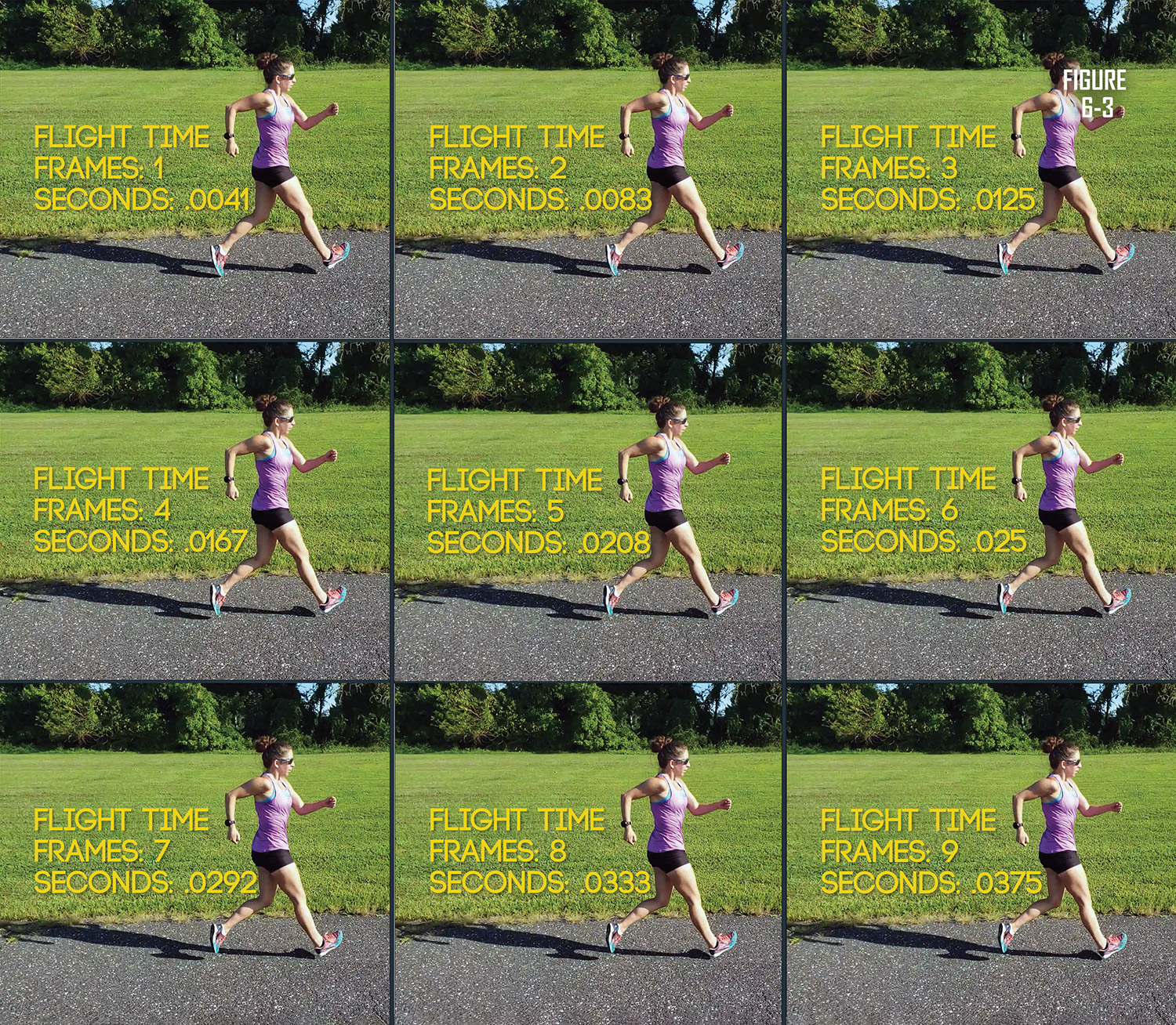

However, the decision of legality becomes blurrier as a race walker’s stride contains a miniscule loss of contact phase. Through high speed videography, we can easily estimate the flight phase of a walker. The walker shown was shot using a camera capturing 240 frames per second (fps). That means for each frame the walker does not have contact with the ground, their estimated flight time of increases .0041 seconds.

In the old days, when video was recorded on tape, it was recorded at 24-30 frames per second. Therefore, having no contact with the ground for more than 1 frame and less than 2 frames approximated to being off the ground for about .033 seconds and that was considered the threshold for the human eye being able to discern that a person was off the ground. That estimate was subjective. If we use it as a barometer, somewhere between 7 to 8 frames of flight with a 240 fps camera is probably not detectable by the human eye.

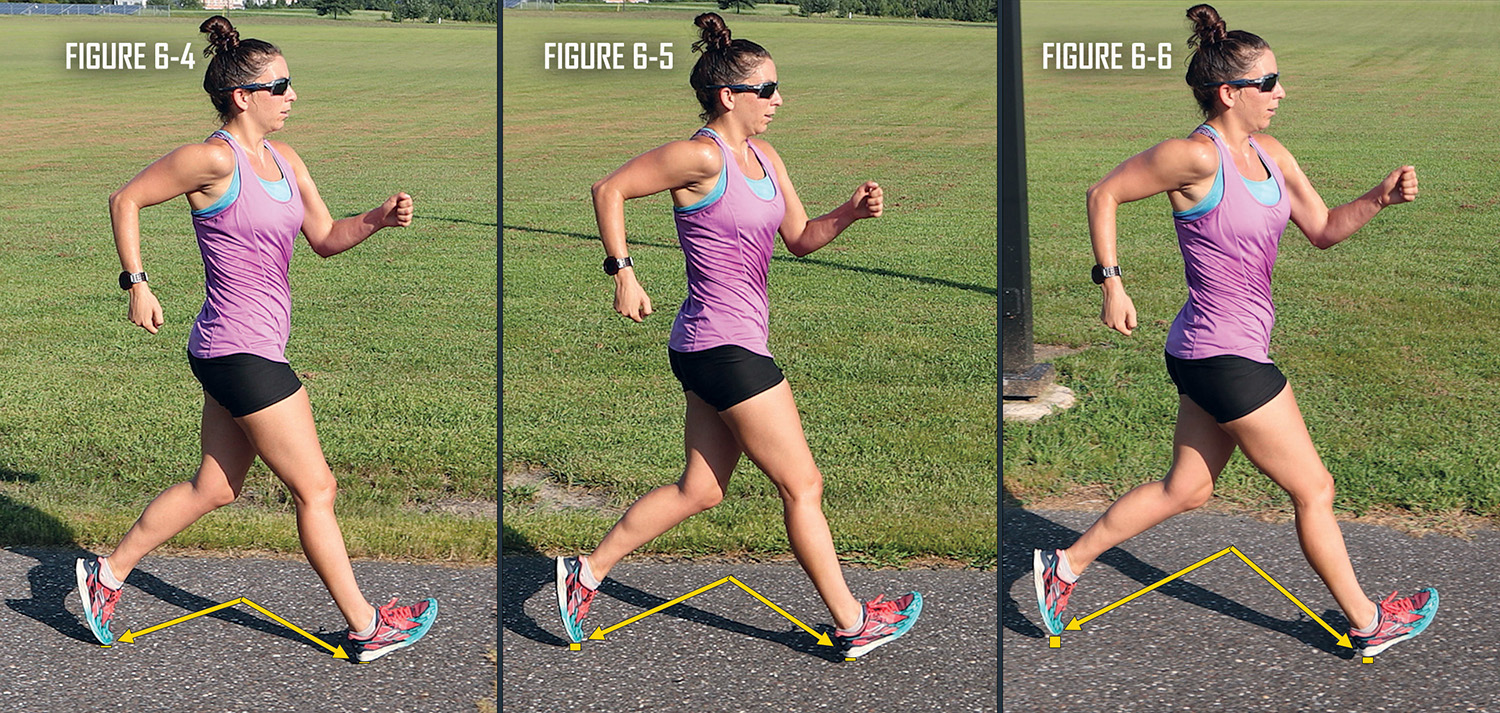

First, let’s observe walkers with varying flight times. While it’s not fair to judge from a still photo, we can still have an objective conversation about the following three images.

The walker in Figure 6-4 is barely off the ground. While there is a flight phase visible to the camera, it’s not noticeable to even the keenest human eye. The walker in Figure 6-5 has lost contact for 4-5 frames. While an individual judge’s optical acuity varies, it’s probably safe to say that this would not be noticeable by the human eye. The walker in Figure 6-6 is off the ground by more than 8 frames. So, she is closer to being deserving of being disqualified, but still may not be above the threshold to be seen by the human eye.

To some, this may seem excessively generous. Judges have a very difficult job and that’s why in most cases it requires more than one judge to disqualify a walker.

In the presentation, Kinematics of Elite Race Walking, Brain Hanley studied race walkers at the 2008 World Cup. 30 20Km men’s flight times were measured. While 3 had no visible flight phase, 15 had at least .02 seconds of loss of contact and 12 had a loss of contact for at least .04 seconds. These measurements were made with a 50 fps camera, so the athlete’s flight times could be almost .02 seconds greater than measured. You might be questioning if .04 seconds is too generous. However, none of the walkers studied were disqualified. So, it may be that our estimate of .033 seconds is significantly less that what trained judges can detect.

If you are new to race walking, unless you come from a very athletic background, you probably won’t be losing contact with the ground initially.

If you have concern, you can either enter a race and see how you do, or you can have someone video you with a high frame rate camera, even a smart phone, and count the frames. Just do it in really bright light to help the camera expose your feet clearly.

Correcting Loss of Contact

While it’s easy to just say “slow down,” there are many aspects of your stride that you can focus on instead of just slowing down.

If you can master these changes, then you might not have to slow down much, if at all, to reduce the perception that you are lifting.

While you may not be higher off the ground than the walker next to you, if you have excessive motion throughout your body you may draw the unwanted attention of judges.

Bouncing shoulders, bobbing heads, and arms flailing about are all unnecessary and inefficient. In addition to wasting energy, they can contribute to the perception that you are significantly off the ground. Judges should not determine if you are violating the definition based on excessive motion, but they may use it as a reason to observe you more closely.

Focus on quieting your body. Try walking in front of a mirror on a treadmill while reducing excessive body motion. Focus on going forward, not up, down, or side to side. The instant feedback received by walking before a mirror goes a long way to improving your form.

A big problem for walkers who get calls for lifting is the manner in which they carry their leg as it swings forward. A low foot and knee carriage as the leg swings forward is crucial to efficient technique. It is also pivotal to appearing legal.

Walkers who gallop forward, driving their knee high, inadvertently drive their foot forward higher off the ground. The difference may only be a matter of an inch or two, but that difference appears dramatic to a judge.

Observe Figures 6-8 and 6-9 where Miranda simulates a slight change in style by driving the knee higher. When we draw a horizontal line at heel height, we can see she is carrying her foot higher in Figure 6-8. We can also see other changes to her body position. She unconsciously leans forward and excessively increases the range of motion of her arms.

Focusing on a low vertical position of the foot and knee throughout the leg as it swings forward is one key to reducing your chance of a lifting call.

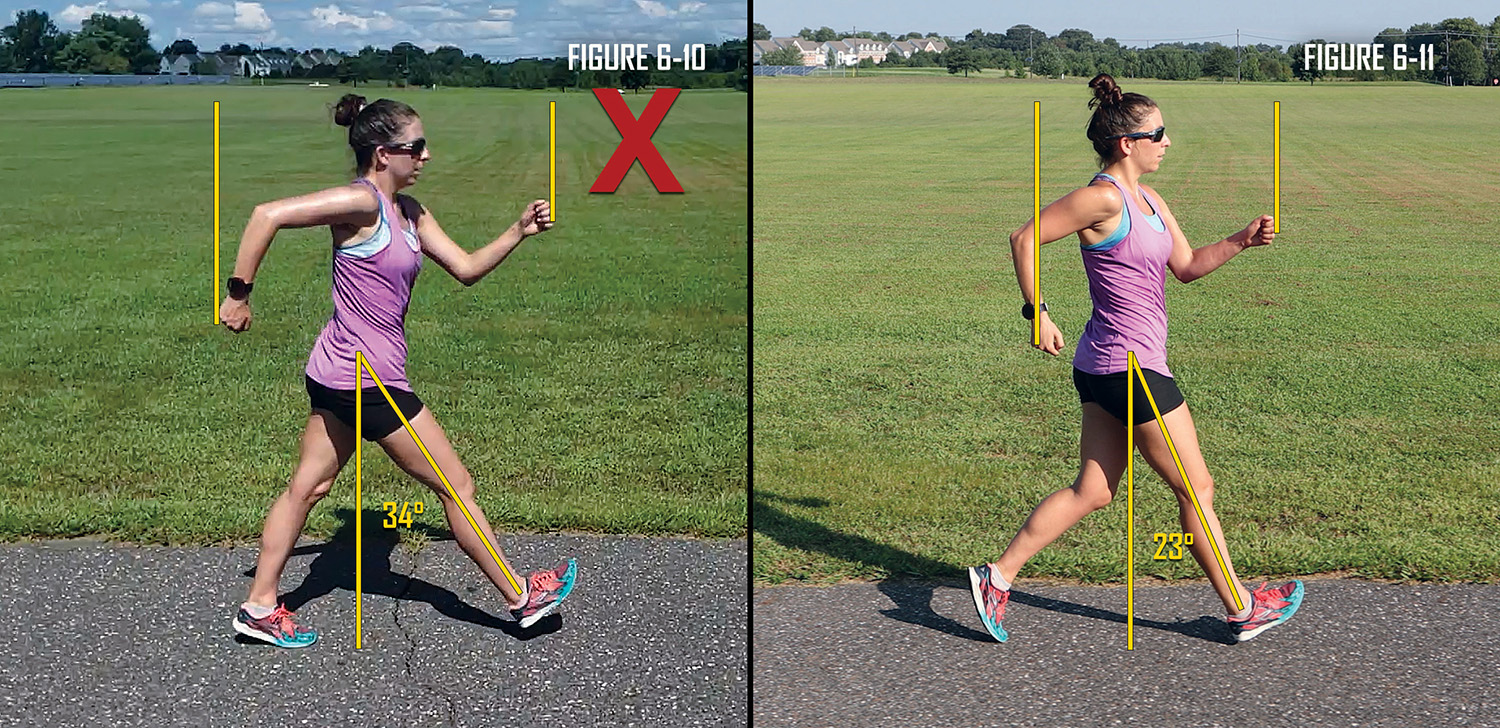

Overstriding in front of the body can also lead to lifting. When you reach out too far in front of your body, your foot hangs in the air, floating for all the judges to see. Often this is caused by swinging your arms too far in front of or behind your body.

Focus on good arm carriage and your legs should come back in line. Alternatively, lifting may be caused by reaching forward with your leg instead of your hips. Concentrate on placing the swing leg down shortly after it passes under the torso.

Observe how when Miranda overstrides in Figure 6-10 her leg is straightened, but she has neither placed her swing foot on the ground nor rolled up on the back foot. In contrast, in Figure 6-11, Miranda’s swing foot strikes the ground simultaneously with her leg straightening and her rear foot rolling up onto it’s toes. You can also observe that when she overstrides the angle that her leg extends from the body is greater, thus leading to an undesirable braking action.

In addition to focusing on the key mental aspects causing lifting, you can also address the physical causes that lead to a visible flight phase. Two of the main offenders are a lack of hip flexor range of motion and tight hamstrings. Practicing the following exercises greatly improves your range of motion and assists in lengthening your stride behind your torso.

Next Lesson: Exercises to Correct Excessive Loss of Contact in Race Walking